My takeaway from listening to dozens of F500 earnings calls: The need for “elasticity mapping”

In recent weeks, I’ve spent much of my time listening to hour-long Fortune 500 quarterly earnings calls… yes, really. From my short stint in communications, I’ve become acutely aware of how much can be learned about a leadership team’s priorities from their carefully crafted intro statements on these calls. Even further, analyst questions give a nice snapshot of the challenges they’re pulling their hair out over on a daily basis.

The areas covered are generally unsurprising. Up top the list are inflation, issues getting supplies, COVID-19 response, labor issues, and building & maintaining capacity. Yet, most-to-all have a common theme, sometimes mentioned explicitly and other times implicitly – supporting cost increases with price (“x”) increases. I will describe the “x” factor later on.

In (theoretical) markets with unlimited competition and perfect information for all participants, supply shocks force companies to reorganize their supply chains to the next lowest marginal cost arrangements (and, based on theory, grow in size to a minor extent), increasing costs but only infinitesimally. The simple presence of inflation does not affect productivity under these assumptions for the same reason a stock split does not affect a company’s market cap… currency is diluted. Cost increases are matched with price increases.

In the real world however, barriers to entry exist. Information problems exist. Markets are not perfect, and many companies are struggling to minimize upstream cost increases and further, to pair them with downstream price increases.

Think – industrial companies with a relatively concentrated book of business. Consumer products companies facing stiff competition for customers, and a supply chain that is tied up in increasing-transaction cost geographies. Financial services firms dealing with new labor issues on the one hand, and new competition on the other.

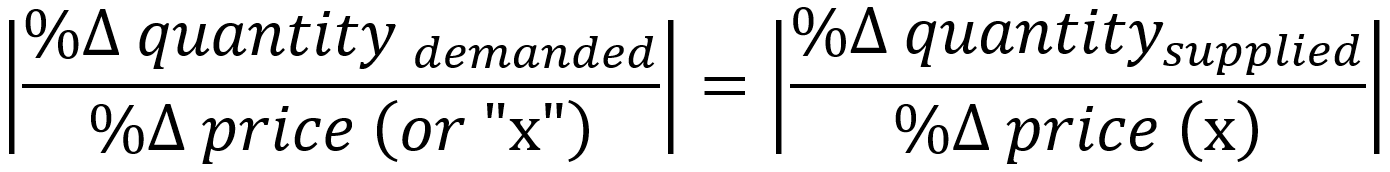

All are struggling to equalize, or at least optimize the difference between, elasticity measures in the supply base with those in one’s own. That is, simply:

(Absolute values are used as demand elasticity is negative – that is as price increases, quantity demanded decreases.)

(It is generally the Lerner index, [P-MC]/P or -1/ε, that researchers use to measure a firm’s ability to raise prices. Here, we achieve the same by using elasticity directly.)

Getting this type of logic on paper is useful, and its application is clear… demand and supply elasticities, at least as it relates to price, can be estimated quantitatively without much difficulty. “Elasticity mapping” can be performed at the procurement category, geography, product, or customer level. Wrapped up in elasticity measures are also individual transaction costs, barriers to entry, geopolitical issues, and other current state variables. What’s more, external changes can be proactively incorporated into these models so as to prepare for the impact of, for example, a pandemic, a war, new regulations, or other developments.

Supply shocks destroy resources upstream, reducing competition and decreasing a company’s elasticity of supply. It will be relatively harder to pair cost increases with price increases, especially in the areas most affected.

In the case of a pandemic, we would expect goods markets to be significantly impacted compared with services markets. A number of actions to potentially take away here. Perhaps supply chain teams will vertically integrate in critical goods markets by converting contractors into FTEs, extending MSA durations, or acquiring existing plants. Perhaps they will transition sourcing activities to suppliers in geographies with more predictable policymaking. Or perhaps, if nothing else, they will simply increase their procurement headcounts in those areas most likely to be affected.

Finally, why do we care about “x”-elasticities rather than just price-elasticities? Because price is only one determinant of buying behavior, and it is a decreasingly significant one in some markets. Reducing the relative importance of price are factors such as company reputation, ESG considerations, onboarding costs, information problems, and possibly idiosyncratic timing issues. The same principles apply. In competing for a monopsony buyer, for example, companies will be forced to invest more in ESG than they are able to demand from their relatively competitive suppliers.

“Elasticity mapping” is just one very broad way in which functional teams can use economic models and metrics to improve day-to-day decision making. Further, start from this research topic and there exists a huge stock of literature, including theory and empirical work, expanding on these ideas much more in-depth that I can here.

At Sourced Economics, we’re working hard to apply these concepts for practical use by professionals across supply chain, finance, technology… strategy broadly. Feel free to reach out via john@sourcedeconomics.com with questions, or to schedule a call to learn more.